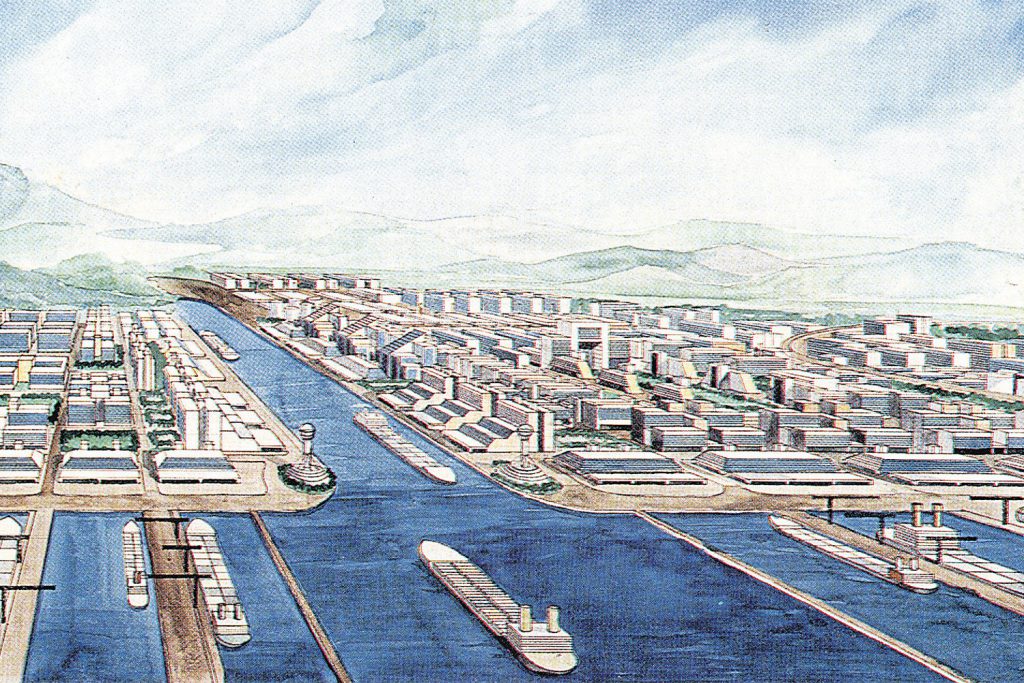

Kra Canal is the main transportation route used by Chinese merchants to transport goods in the Indian Ocean through the ancient sea routes.

Guest Column by D A Hettiarachchi

Indian Ocean region and the vast landscape situated encircling the Ocean are considered to be one of the world’s prominent hubs for sea trade since the bygone era. The notable reason for the significance of the Indian Ocean is the abundance of the trade route that connects the western and the eastern hemisphere, easing the trade activities that encompass the entire world.

Amidst these sea trade activities that took place between the nations, India and Sri Lanka were main actors in the transactions. China too, expanding its territorial integrity, attempted to use the Kra canal in Thailand to extend its sea trade in the Indian Ocean region instead of using the Sea Strait of Malacca that was prominently used for sea trade at that time.

This research paper is compiled as a comprehensive study carried out through archaeological reference materials and historical studies about the nature of the sea trade activities that have been carried out in the Indian Ocean region through Kra canal.

The importance of the Indian Ocean as a Centre for Inter-Exchanges between the East and the West

The Indian Ocean is surrounded by Asia, Africa, Australia and Antarctica at a mass stretch doubling the advantage of the sea. In the landscapes of these regions, there are visible remarks of the development of sea trade activities that took place along the sea route and the abundance of sea ports which were developing ever since.

Before man began the agricultural cultivations there is proof that they have engaged in sea trade activities in land areas, coastal regions and estuaries (Fuller, 2011). It has been clear that the commencement of transportation through the sea routes have been centralised upon the people living in the West and the East. As evidences it has been found out that the civilisations have been starting from the 1st Century B.C. with the man’s sea explorations from the Northern Asian regions to Australia. Wood has been used to create the merchant ships to trespass the oceans and to exchange goods such as yams, coconut, plantains, sugar cane and other endemic plants. (Pearson, 2003; Kearney, 2004; Bushman, 2007; Silva, 2013; Ranawella, 2014)

In the Western parts of the Indian Ocean region there are written evidences to prove the starting of the sea trade activities by the people belonging to the Egyptian, Mesopotamian and the Indus river valley civilisations. From the artifacts and the documents found by Mesopotamia during the 4th and 3rd Century B.C. it is seen that people have started sea trade activities in the Gulf of Arab region.

With the upward social mobility that was evident at that time with the development of the civilisations, the need for goods and services became a required necessity. Among those goods were the luxurious commodities. The raw materials included types of stones, wood, metals required to build military equipment used for war and various decorative clay vessels were able to draw the attention of the vendors and the imperial community during the contemporary time (Pearson, 2003; Kearney, 2004; Bushman; 2007).

By the 1st Century B.C., the written proofs and legends have proved about the sea trade activities that have taken place in the Indian Ocean region. The facts regarding the development of the prolonged sea travels are reported to have been taken place during the 1000th Century B.C. and the 300 A.D. whereas the function of the monsoonal winds in the Indian Ocean are found during the 3rd Century B.C. although authenticated statistical data of the monsoonal wind transmission found during the 1000 B.C.

With these findings the contemporary sailors have been able to trespass the Arab Sea with the knowledge of the monsoonal winds and astrology. Similarly in the 2nd and the 3rd Century B.C. there has been proof that the Indian and the Arabian merchant ships have travelled from Southern Arabia to Malabar coast and returned back to Arabia (Seland, 2013; Guan, 2016)

According to the historians the long distant sea trade activities that took place between Egypt and the Mesopotamian civilisations gradually declined during the 1000 B.C. The group that engaged in the sea trade activities in the Indian Ocean during the second half of the 1st Century B.C. comprised of Greek and Roman salesmen. The historical document which was known as the “Periplus of the Erythraean Sea” gives the information regarding the ports, nations and the types of goods and commodities exchanged in trade activities of the Indian Ocean region. Among those information are the details about East Africa and India. This provides ample evidence in understanding that the merchants of the Mediterranean have reached to an already developed sea trade zone to promote their products (Chaudhuri, 1985; Matthew, 2011).

The merchants of China and East Asia have carried out sea trade activities with India whereas India has also exported many commodities while importing metals of higher value such as silver, copper and gold. With the coins belonging to the Maurya tradition, Persia, Rome and the Han dynasty in China it is proven that the East and the West have been prominent zones for inter- exchanges.

Clothing, clay vessels. metallic items, glass, pearls, aromatic items, rare furniture, spices, stones and corals have been the common goods that have been transporting in the Indian Ocean region. With that, the Indian and the Sri Lankan ports that are located in the Indian Ocean region have been considered as a major centre for the exchange of goods and commodities of China from the East whereas goods of Greece, Persia and Rome from the West (Carswell & Prickett, 1980; Siriweera, 2013; Silva, 2013; Kelegama, 2014).

Sri Lanka, having its geostrategic location in the centre of the international maritime route has been playing its role as a sea port for mooring merchant ships, centre for providing assistance for merchant ships and a centre for inter-exchanges as for the evidences provided by historical and archaeological artifacts.

For the last 3000 years there have been mini vessels and larger merchant ships coming from Asian regions such as China and Malaysia and Arabian regions such as Rome. Some ports among these developed into the establishment of specific centers in the Maritime Silk Route and the city of Manthai in Sri Lanka is one such commercial cities established in Sri Lanka (Perera,1992 ; Siriweera, 2013 ; Silva,2013 ; Kelegama,2014 ; Ranawella,2014 ; Sirisena, 2016).

A popular region trespassed by the merchant ships that were sailing from China when reaching the trade zone around the Indian Ocean is Thailand. The goods of Thailand or also known as Siam have been transported to India and Sri Lanka through the Chinese merchants. The purpose of this study has been to find out the historical phenomena related to the sea trade activities between Sri Lanka, the Indian Ocean region and China that prevailed from the ancient times as well as to find out the incidents that directed in the construction of the modern Kra Canal.

Kra Canal Route and Ancient Trade Activities in the Indian Ocean

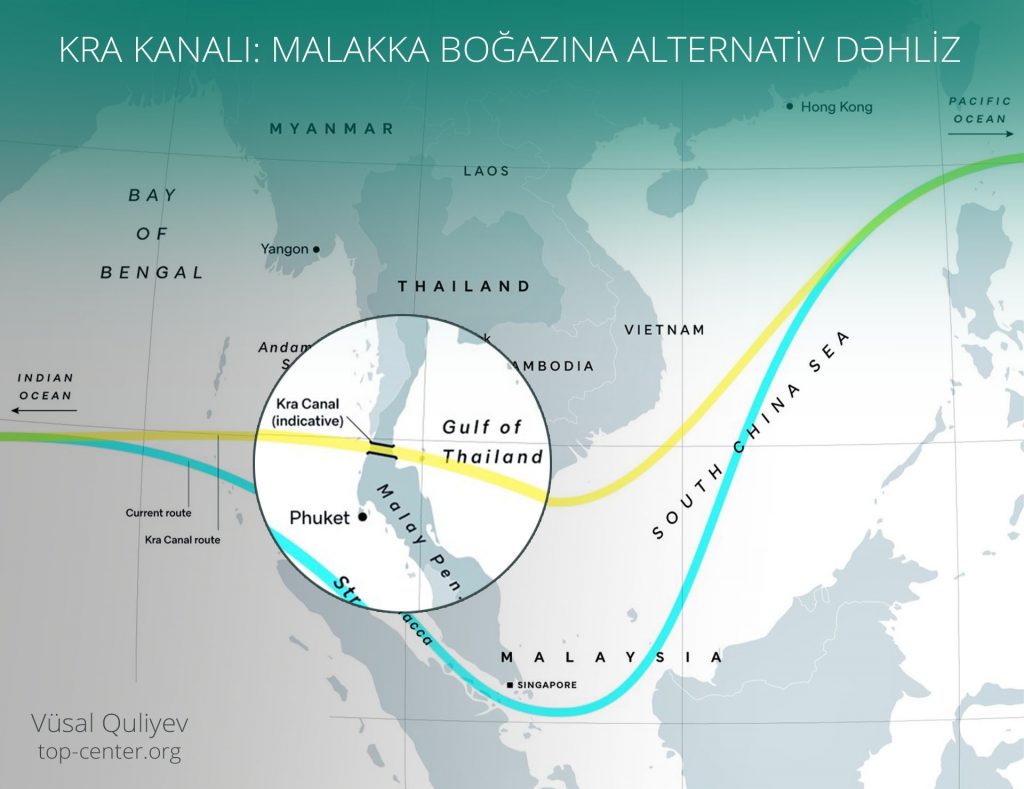

Kra Canal is the main transportation route used by the Chinese merchants to transport goods in the Indian Ocean through the ancient sea routes. This canal is situated in the narrowest place that separates the Andaman Sea and the Gulf of Thailand towards the Malay hemisphere which is also known as the Kra Isthmus.

During the 4th and the 5th Century A.D., it has been found that 12 ports including Takuapa, Tavoy, Ranong and Singgora have been operated adjoining the existing sea routes (Kit,2012 ; Kinder,2007). It can be assumed that these ports have been used by the Chinese merchant ships as mooring station during the contemporary time.

From the results obtained by the Siam Society on the archaeological investigations, it has been clarified that crossing the Kra Canal for transportation purposes was chosen over crossing through the Sea Strait of Malacca that entailed a numerous amount of accidents for the merchant ships in the route from the Pacific Ocean to the Indian Ocean (Thongsin,2002 ; Dobbos,2016 ; Chen & Kumagi,2016).

From the archaeological information provided by the Siam Council in 1930 it was revealed that travelling through the narrow land area across the Kra Isthmus was chosen than travelling through the high risk zone of the India Ocean. According to a report by John Crawfurd, elephants have been used as a mode of transportation in the land areas across the Kra Isthmus and smaller vessels have been used to cross the minor canals while 5-8 days were taken to cross these areas by them (Chen & Kumagi, 2016).

Although there have been various proposals as to broaden this natural reservoir for the ease of travelling by the huge merchant ships, the ancient kings of Thailand such as King Narai of Ayutthaya (1629 A.D – 1688 A.D) and King Rama I (1782 A.D. – 1809 A.D.) have initiated the discussion of the restoration of the Kra Canal (Kit,2012). The historical investigations prove that this idea of restoring the Kra Canal has come into consideration at various points during the 19th Century.

As a result of that, during the reign of King Rama III or also known as King Phra Nangklao (1824 A.D. – 1851 A.D.), King Rama IV or also known as King Mongkut (1851 A.D. – 1868 A.D.) and King Rama V or also known as King Chulalongkorn (1868 A.D. – 1910 A.D.), the Europeans have communicated the idea of Kra Canl for Siam. With the displeasure of the Siamese about Europe’s involvement in the position of Kra Canal, the proposal to restore the Kra Canal has been dismissed (Figure 3) (Thongsin,2002 ; Dobbos.2016 ; Chen & Kumagi,2016).

One of the most successful kingdoms of Thailand was the kingdom of Ayutthaya or Ayodhya that was established in the 1350 A.D. whereas Thailand has been known as Siam during this time. The city of Ayutthaya has been situated in a rich fertile land near the Chao Phraya river and this city has been flourishing as one of the greatest nations in the East during the 15th Century B.C. By the 16th Century B.C. Ayutthaya has become a prominent trade centre in the zone. As a result of these the Portuguese and the Dutch have landed to Siam by the 16th Century B.C.

With the rapid development of the sea trade activities that occurred with the arrival of these nations for Siam, the need for broadening the Kra Canal across the Kra Isthmus arose. The idea of this arose for the first time during the reign of King Narai by the French engineer called M. De Lamar and he has also shown the possibility of constructing a road linking Songkhla in Thailand and Tavoy in Burma. The idea was also dismissed due to the existence of a mountainous region in Kra Isthmus (Thongsin,2002 ; Dobbos,2016).

Sea Strait of Malacca is one of the busiest sea straits in the modern time. This sea strait is located adjoining the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean. With the consequent development of the modern world in various spheres with the progress of globalisation, economic unification and the dispersion of international trade activities, there has been a remarkable growth in the international transportation methods.

Although there is a disruptive growth in the maritime transportation systems there is a huge traffic among the marine vessels and as a result of that many threats such as collision between vessels, threats from smugglers, the increase of marine pollution and the threats caused for the marine life are among the major threats that are caused. As for Napa and the team (2008) it was found that the restoration of the Kra Canal can be used as an alternative solution in order to avoid the threats caused for the marine bio-diversity.

Conclusion

In the ancient world, the main sea trade route that linked the East and the West is the Maritime Silk Route. The development of this sea route has been progressing over the years from the late Century B.C. and one of the notable features have been that the merchants of the East and the West have brought their goods and commodities for the ports near the Indian Ocean region whereas they have exchanged the items at the same place. As a result of that, several commercial cities that aided in the services for the sailors of Sri Lanka and India were created.

Similarly, the Kra Canal which was situated in the Southern Thailand has been equally important as same as that of the Sea Strait of Malacca which was used to transport goods and commodities from the East Asia to China and Japan for the ports in the Indian Ocean region. The significant factor for the Kra Canal to be of major importance in the trade and transportation activities was the absence of threats for the sailors in crossing the Sea Strait of Malacca.

Although it was evident that there has been modern approaches proposed for the development of the Kra Canal, from the 4th Century B.C., the Kra Canal has been recognised as a trade route that adjoined two oceans as concluded by this research study.

Moreover, it can also be stated that through the development project of broadening the Kra Canal, a nation like Sri Lanka which is situated in the centre of the Indian Ocean can be strategically utilised so as to get the benefits as a centre for inter-exchanges and maritime services. Through this research it is thus concluded that the fact about the geostrategic importance of the Kra Canal is found in the written history.

(The writer is from the Faculty of Post Graduate Studies, University of Sri Jayewardenepura.)

References

Ranawella S. (2014) Purathana Sri Lankawe Arthika Ithihasaya. Visidunu Publushers, Boralesgamuwa.

Bushman R. F. (2007). Oceans in World History. MacGraw-Hill, Boston. Carswell J. and Prickett M. F. (1980) Mantai 1980 a preliminary investigation. Ancient Ceylon 5, 7-65.

Chaudhuri K.N. (1985). Trade and Civilisation in the Indian Ocean: An Economic History from the Islam to 1750. Cambridge University Press, UK.

Chen C. & Kumagai S. (2016). Economic Impact of the Kra Canal: An Application of the Automatic Calculation of Sea Distance by a GIS. Institute of Developing Economies.

Dobbos S. 2016). Thailand’s isthmus and Elusive Canal Plans since 1850s. Trans- Regional and National Studies of Southeast Asia 4(1), 165-186.

Fuller D. Q (2011). Across the Indian Ocean: The Prehistoric Movement of Plants Animals. Antiquity 85(328), 544-558.

Guan K.C. (2016). The Maritime Silk Road: History of an Idea. NSC Working Paper 23, 1- 20.

Kearney M. (2004). The Indian Ocean in World History. Routledge, New York.

Kelegama S. (2014). China-Sri Lanka Economic Relations: An Overview. China Report 50(2), 131-149.

Kinder I. (2007). Strategic Implications of the possible construction of the Thai Canal. Croatian International Relations Review 593, 109- 118.

Kit C. N. Y. (2012). Kra Canal (1824-1910): The Elusive Dream. Akademika 82(1), 71-80.

Matthew P.F. (2011). Provincializing Rome: The Indian Ocean Trade Network and Roman Imperialism. Journal of World History 22(1), 27-54.

Peable P. (2006). The history of Sri Lanka. Greenwood press, London.

Pearson M. N. (2003). The Indian Ocean. Routledge, London.

Perera B.J. (1992). The location of Mahatittha. RAS (CB) xxxvii, 107-115. Premathilaka P.L. (2003) China ceramic discovered in Sri Lank an overview. In Sri Lanka and the Silk Road of the sea. (Bandaranayeke S., Dewaraja L., Silva

R. & Wimalarathne K.D.G., eds), Central Cultural Fund, Sri Lanka, 225-236.

Rahman N. S. F. A., Salleh N. H. M., Najib A. F. A. & Lun V. Y. H. (2016). A descriptive method for analysing Canal decision on maritime business patterns in Malaysia. Journal of Shipping and Trade 1(13), 1-16.

Ranasinghe G. (2013). Maritime Cultural Interaction between Sri Lanka and China- Based on Archaeological Artifacts of both Countries. PhD Thesis, Xiamen University, China.

Ranasinghe G. and Chindima A. (2012). A study of Chinese coins in Sri Lanka. Proceeding of Maritime cultural heritage new progress and archaeological discipline. Xiamen University, China, 206-226.

Seland E.H. (2013). Network and social cohesion in ancient Indian Ocean trade: geography, ethnicity, religion. Journal of Global History 8, 373-390.

Silva K.M. de (2008). A History of Sri Lanka. Vijitha Yapa Publication, Colombo 04.

Silva N. D. (2013). Literary References: Ports of Historical and Spiritual Contacts. In Fernando, S. (editor) Maritime Heritage of Sri Lanka. The National Trust, Sri Lanka. 30-38.

Sirisena W.M. (2016). Sri Lanka and South-East Asia. S. Goadage and Brothers (Pvt) Ltd, Colombo 10.

Siriweera W. I. (2013). Maritime Commerce and Ports in Ancient Sri Lanka. In Fernando, S. (editor) Maritime Heritage of Sri Lanka. The National Trust, Sri Lanka. 82-90.

Thapa R. B., Kusanagi, M., Kitazumi, A. & Murayama, Y. (2008). Sea navigation, challenges and potentials in South East Asia: an assessment of suitable sites for a shipping canal in the South Thai Isthmus. Geo Journal 70, 161-172.

Thongsin A. (2002). The Kra Canal and Thai Security. Masters Thesis. Naval Postgraduate School, California.

University of Ceylon (1959). History of Ceylon. Ceylon University Press, Colombo.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the publisher